You'll find it easiest to read this chapter (and those following that discuss more widgets) in order. Because there is so much commonality between many widgets, we'll introduce certain concepts when describing one widget that will also apply to a widget we describe later. Rather than going over the same ground multiple times, we'll refer back to when the concept was first introduced.

As each widget is introduced, we'll refer to the widget roundup page for the specific widget, as well as the Tk reference manual page. As a reminder, this tutorial highlights the most useful parts of Tk and how to use them to build effective modern user interfaces. The reference documentation, which details everything that can be done in Tk, serves a very different purpose.

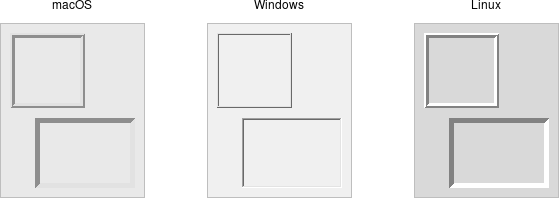

Frame

Frame widgets.

A frame is a widget that displays as a simple rectangle. Frames help to organize your user interface, often

both visually and at the coding level. Frames often act as master widgets for a geometry manager like grid,

which manages the slave widgets contained within the frame.

Frames are created using the ttk.Frame class:

frame = ttk.Frame(parent)Frames are created using the ttk::frame command:

ttk::frame .frameFrames are created using the Tk::Tile::Frame class:

frame = Tk::Tile::Frame.new(parent)Frames are created using the new_ttk__frame method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__frame():

$frame = $parent->new_ttk__frame;Frames can take several different configuration options, which can alter how they are displayed.

Requested size

Typically, the size of a frame is determined by the size and layout of any widgets within it. In turn, this is controlled by the geometry manager that manages the contents of the frame itself.

If, for some reason, you want an empty frame that does not contain other widgets, you can instead

explicitly set its size using the

width and/or height configuration options (otherwise, you'll end up with a

very small frame indeed).

frame['width'] = 500

frame['height'] = 400.frame configure -width 500

.frame configure -height 400frame['padding'] = '500'

frame['padding'] = '400'$frame->configure(-padding => "500");

$frame->configure(-padding => "400");Remember, you can request a given size for a frame (or any widget), but the geometry manager has the final say. If you're wondering why a widget isn't displayed at the same size you requested, that's why.

Specifying screen distances

When we asked that the frame be "500" wide, how big is that? What are the units? If not otherwise specified, screen distances such as width and height (and others, like padding and borderwidth below) are measured in pixels. So when we ask that a frame be "500" wide, we're requesting 500 pixels.

You can also specify a number of different units for screen distances by appending one of several suffixes to the number. For example, 350 means

350 pixels, 350c means 350 centimeters, 350m means 350 millimeters, 350i means 350 inches, and 350p means 350 printer's points (1/72 inch).

While if we're specifying pixels we may have passed the screen distance as an integer, when we use one of these different units, we're passing the screen distance as a string.

frame['width'] = '500p' # 500 points (just under 7 inches).frame configure -width 500p ;# 500 points (just under 7 inches)frame['padding'] = '500p' ;# 500 points (just under 7 inches)$frame->configure(-padding => "500p"); # 500 points (just under 7 inches)Tk programs almost always specify screen distances as pixels… and you can see why. It's the default, and we don't even have to think about converting between integers and strings. Mostly, it works. But is it the best way to specify distances? Probably not. With today's high resolution monitors and different display scaling resolutions users can select, the same number of pixels may look very different on two different displays. Using points is probably a better bet, as it takes into account scaling. Another good option might be to base screen distances on the size of a standard font, like we do in HTML when we specify units as "em" or "rem." Unfortunately, Tk doesn't offer this as a built-in option like it does for points, millimeters, centimeters, and inches. But if you want to calculate such distances yourself, you'll see in the Fonts chapter how to determine how many pixels are required to render a given string (like "m") in a given font.

Padding

The padding configuration option is used to request extra space around the inside of

the widget. If you're putting other widgets inside the frame, that provides a margin between the frame's border and the widgets within.

You can specify the same padding for all sides, different horizontal and

vertical padding, or padding for each side separately.

frame['padding'] = 5 # 5 pixels on all sides

frame['padding'] = (5, 10) # 5 on left and right, 10 on top and bottom

frame['padding'] = (5, 7, 10, 12) # left: 5, top: 7, right: 10, bottom: 12.frame configure -padding 5 ;# 5 pixels on all sides

.frame configure -padding "5 10" ;# 5 on left and right, 10 on top and bottom

.frame configure -padding "5 7 10 12" ;# left: 5, top: 7, right: 10, bottom: 12frame['padding'] = '5' ;# 5 pixels on all sides

frame['padding'] = '5 10' ;# 5 on left and right, 10 on top and bottom

frame['padding'] = '5 7 10 12' ;# left: 5, top: 7, right: 10, bottom: 12$frame->configure(-padding => "5"); # 5 pixels on all sides

$frame->configure(-padding => "5 10"); # 5 on left and right, 10 on top and bottom

$frame->configure(-padding => "5 7 10 12"); # left: 5, top: 7, right: 10, bottom: 12Borders

You can display a border around a frame widget to visually separate it from its surroundings.

You'll see this often used to make a part of the user interface look sunken or raised. To do this,

you need to set the borderwidth configuration option (which defaults to 0, i.e., no border)

and the relief option, which specifies the visual appearance of the border. This can be one of:

flat (default), raised, sunken, solid, ridge, or groove.

frame['borderwidth'] = 2

frame['relief'] = 'sunken'.frame configure -borderwidth 2 -relief sunkenframe['borderwidth'] = 2

frame['relief'] = 'sunken'$frame->configure(-borderwidth => 2, -relief => "sunken");Changing styles

Frames have a style configuration option, which is common to all of the themed widgets.

This lets you control many other aspects of their appearance or behavior. This is a bit more

advanced, so we won't go into it in too much detail right now. But here's a quick example of creating a "Danger"

frame with a red background and a raised border.

s = ttk.Style()

s.configure('Danger.TFrame', background='red', borderwidth=5, relief='raised')

ttk.Frame(root, width=200, height=200, style='Danger.TFrame').grid()ttk::style configure Danger.TFrame -background red -borderwidth 5 -relief raised

grid [ttk::frame .f -width 200 -height 200 -style Danger.TFrame]Tk::Tile::Style.configure('Danger.TFrame', "background" => "red", "borderwidth" => 5, "relief" => "raised")

f = Tk::Tile::Frame.new(root) {width 200; height 200; style "Danger.TFrame"}.grid()Tkx::ttk__style_configure("Danger.TFrame", -background => "red", -borderwidth => 5, -relief => "raised");

my $f = $mw->new_ttk__frame(-width => 200, -height => 200, -style => "Danger.TFrame")->g_grid();What elements of widgets can be changed by styles vary by widget and platform. On Windows and Linux, it does what you'd expect. On current macOS, the frame will have a red raised border, but the background will remain the default grey. Much more on why this is in a later chapter.

We discussed the change from options to styles previously in the Concepts chapter, but it's worth a reminder. Styles mark a sharp departure from how most aspects of a widget's visual appearance were changed in the "classic" Tk widgets. In classic Tk, you could provide a wide range of options to finely control every aspect of an individual widget's behavior, e.g., foreground color, background color, font, highlight thickness, selected foreground color, and padding. When using the new themed widgets, these changes are made by modifying styles, not adding options to each widget.

As such, many options you may be familiar with in certain classic widgets are not present in their themed version. However, overuse of such options was a key factor undermining the appearance of Tk applications, especially when used across different platforms. Transitioning from classic to themed widgets provides an opportune time to review and refine how (and if!) such appearance changes are made.

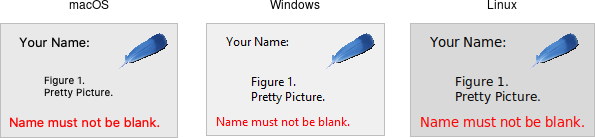

Label

Label widgets.

A label is a widget that displays text or images, typically that users will just view but not otherwise interact with. Labels are used to identify controls or other parts of the user interface, provide textual feedback or results, etc.

Labels are created using the ttk.Label class. Often, the text or image the label will display are

specified via configuration options at the same time:

label = ttk.Label(parent, text='Full name:')Labels are created using the ttk::label command. Often, the text or image the label will display are

specified via configuration options at the same time:

ttk::label .label -text {Full name:}Labels are created using the Tk::Tile::Label class. Often, the text or image the label will display are

specified via configuration options at the same time:

label = Tk::Tile::Label.new(parent) {text 'Full name:'}Labels are created using the new_ttk__label method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__label().

Often, the text or image the label will display are specified via configuration options at the same time:

$label = $parent->new_ttk__label(-text => "Full name:");Like frames, labels can take several different configuration options, which can alter how they are displayed.

Displaying text

The text configuration option (shown above when creating the label) is the most commonly used, particularly when

the label is purely decorative or explanatory. You can change what text is displayed by modifying this configuration option.

This can be done at any time, not only when first creating the label.

You can also have the widget monitor a variable in your script. Whenever the variable changes, the label will automatically update to

display the new value of the variable. We saw this before in our feet to meters example. This is done with the textvariable configuration option:

resultsContents = StringVar()

label['textvariable'] = resultsContents

resultsContents.set('Initial value to display')Tkinter only allows you to attach widgets to an instance of the StringVar class but not arbitrary Python variables.

This class contains all the

logic to watch for changes and communicate them back and forth between the variable and Tk. Use the get and set methods

to read or write the current value of the variable.

current = resultsContents.get()

resultsContents.set('New value to display).label configure -textvariable resultContents

set resultContents "Initial value to display"Variables must be global, or the fully qualified name given for those within a namespace.

$resultsVar = TkVariable.new

label['textvariable'] = $resultsVar

$resultsVar.value = 'Initial value to display'Ruby's Tk binding only allows you to attach to an instance of the TkVariable class, which contains all the

logic to watch for changes, communicate them back and forth between the variable and Tk, and so on. You

need to read or write the current value using the value accessor, as shown.

$label->configure(-textvariable => \$resultContents);

$resultContents = "Initial value to display";Displaying images

Labels can also display an image instead of text. If you just want a static image displayed in your

user interface, this is normally the way to do it. We'll go into images in more detail in a later chapter,

but for now, let's assume you want to display a PNG stored in a file on disk. This

is a two-step process. First, create an image "object." Then, tell the label to display that object

via its image configuration option:

image = PhotoImage(file='myimage.png')

label['image'] = imageimage create photo imgobj -file "myimage.png"

.label configure -image imgobjimage = TkPhotoImage.new(:file => "myimage.png")

label['image'] = imageTkx::image_create_photo( "imgobj", -file => "myimage.png");

$label->configure(-image => "imgobj");We'll cover images in a later chapter. Tk supports PNG, GIF, and PPM/PGM by default, though others can be added.

Labels can also display both an image and text at the same time. You'll often see this in toolbar buttons. To do so, use the

compound configuration option, which accepts the following values:

none (default):- display only the image if present; if there is no image, display the text specified by the

textortextvariableoptions text:- text only (ignore any image provided)

image:- image only (ignore any text provided)

center:- text in the center of the image

top:- image above text

bottom:- image below text

left:- image to left of text

right:- image to right of text

Fonts, colors, and more

As with frames, you normally don't want to change things like fonts and colors directly.

If you need to change them (e.g., to create a special type of label), the preferred method would be to

create a new style, which is then assigned to the widget with its style option.

Unlike most themed widgets, the label widget also provides explicit widget-specific configuration options for fonts and colors as an alternative. Again, you should use these only in special one-off cases when using a style doesn't necessarily make sense.

You can specify the font used to display the label's text using the font configuration

option. While we'll go into fonts in more detail in a later chapter, here are the names of some

predefined fonts you can use:

TkDefaultFont:- Default for all GUI items not otherwise specified.

TkTextFont:- Used for entry widgets, listboxes, etc.

TkFixedFont:- A standard fixed-width font.

TkMenuFont:- The font used for menu items.

TkHeadingFont:- A font for column headings in lists and tables.

TkCaptionFont:- A font for window and dialog caption bars.

TkSmallCaptionFont:- Smaller captions for subwindows or tool dialogs.

TkIconFont:- A font for icon captions.

TkTooltipFont:- A font for tooltips.

Because font choices are platform-specific, be careful of hardcoding specifics (font families, sizes, etc.). This is something else you'll see in many older Tk programs that can make them look ugly.

label['font'] = "TkDefaultFont".label configure -font TkDefaultFontlabel['font'] = "TkDefaultFont"$label->configure(-font => "TkDefaultFont");The foreground (text) and background color of the label can also be changed via the foreground and

background configuration options. Colors are covered in detail later, but you can specify them as either

color names (e.g., red) or hex RGB codes (e.g., #ff340a).

label['foreground'] = "red"

label['background'] = "#ff340a".label configure -foreground red

.label configure -background #ff340alabel['foreground'] = "red"

label['background'] = "#ff340a"$label->configure(-foreground => "ref");

$label->configure(-background => "#ff340a");Font and color changes to labels may not be honoured on all platforms. At present, foreground color and font for labels can be changed on macOS, but not background color.

Labels also accept the relief configuration option discussed for frames to make them appear sunken or raised.

Layout

The geometry manager determines the overall layout of the label (i.e., where it is positioned within the user interface and how large it is). Yet, several options can help you control how the label is displayed within the rectangle the geometry manager gives it.

If the box given to the label is larger than the label requires for its contents, you can use

the anchor option to specify what edge or corner the label should be attached to,

which would leave any empty space in the opposite edge or corner. Possible values are

specified as compass directions: 'n' (north, or top edge), 'ne', (north-east, or top right corner),

'e', 'se', 's', 'sw', 'w', 'nw' or 'center'.

label['anchor'] = "nw"Anchor can be specified as a string, like was done here, using constants defined by Tkinter (e.g., NW), or even as a tuple, e.g., (N, W). Use whatever

approach makes sense for you keeping in mind any project or organizational style conventions.

.label configure -anchor nwlabel['anchor'] = "nw"$label->configure(-anchor => "nw");Things not appearing where you think they should? The position and size of the overall label widget may not be what you

think it is. They can be affected by various widget and geometry manager options.

For example, if you're using grid, you may need to adjust the sticky options.

Options on one widget can affect the placement of another, as the geometry manager juggles space to fit all the widgets together.

When debugging, it can help to change the background color of each widget so you know exactly where each is positioned.

Incidentally, this is a good example of those "one-off" cases we just mentioned where you might use configuration options rather than styles

to modify a widget's appearance.

Multi-line labels

Labels can display more than one line of text. To do so, embed carriage

returns (\n) in the text (or textvariable) string. Labels can also

automatically wrap your text into multiple lines via the wraplength option,

which specifies the maximum length of a line (in pixels, centimeters, etc.).

Multi-line labels are a replacement for the older message widgets in classic Tk.

You can also control how multi-line text is justified via the justify option. It

can have the values left, center, or right. If you have only a single line of text, you

probably want the anchor option instead.

Button

Button widgets.

A button, unlike a frame or label, is very much there to interact with. Users press a button to perform an action. Like labels, they can display text or images, but accept additional options to change their behavior.

Buttons are created using the ttk.Button class:

button = ttk.Button(parent, text='Okay', command=submitForm)Buttons are created using the ttk::button command:

ttk::button .button -text "Okay" -command "submitForm"Buttons are created using the Tk::Tile::Button class:

button = Tk::Tile::Button.new(parent) {text 'Okay'; command 'submitForm'}Buttons are created using the new_ttk__button method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__button():

$button = $parent->new_ttk__button(-text => "Okay", -command => sub {submitForm();});Typically, their contents and command callback are specified at the same time the button is created. As with other widgets, buttons accept several configuration options to alter their appearance and behavior, including the standard style option.

Text or image

Buttons take the same text, textvariable (less commonly used), image, and compound

configuration options as labels. These control whether the button displays text and/or an image.

Buttons have a default configuration option. If specified as active, this tells Tk that the

button is the default button in the user interface; otherwise, it is normal. Default buttons are invoked

if users hit the Return or Enter key. Some platforms and styles will draw this default button with

a different border or highlight. Note that setting this configuration option doesn't create an event binding that will make the "Return" or "Enter" key

activate the button; you have to do that yourself.

The command callback

The command option connects the button's action and your application.

When a user presses the button, the script provided by the option is evaluated by the interpreter.

You can also ask the button to invoke the command callback from your application, just as if the user pressed the button. That way, you don't need to repeat the command to be invoked several times in your program. If you change the command attached to the button, you don't need to change it elsewhere too. Sounds like a useful way to add that event binding on our default button, doesn't it?

action = ttk.Button(root, text="Action", default="active", command=myaction)

root.bind('<Return>', lambda e: action.invoke())ttk::button .action -text "Action" -default active -command myaction

bind . <Return> ".action invoke"action = Tk::Tile::Button.new(root) {text "Action"; default "active"; command {myaction}}

root.bind("Return", proc{action.invoke()})$action = $mw->new_ttk__button(-text => "Action", -default => "active", -command => sub {myaction();});

Tkx::bind(".", "<Return>", sub{$action->invoke();});Standard behavior for dialog boxes and many other windows on most platforms is to set up a binding on

the window for the Return key (<Return> or <Key-Return>) to invoke the active button if it exists,

as we've done here. If there is a "Close" or "Cancel" button, create a binding to the Escape key (<Key-Escape>).

On macOS, you should additionally bind the Enter key on the keyboard (<KP_Enter>) to the active

button and Command-period (<Command-.>) to the close or cancel button.

Button state

Buttons and many other widgets start off in a normal state. A button in its normal state will respond to mouse movements, can be pressed, and will invoke its command callback. Buttons can also be put into a disabled state, where the button is greyed out, does not respond to mouse movements, and cannot be pressed. Your program would disable the button when its command is not applicable based on the state of the application at a given point in time.

All themed widgets maintain an internal state, represented as a series of binary flags. Each flag can either be set (on) or cleared (off).

You can set or clear these different flags, and check the current setting using the state and instate methods.

Buttons make use of the disabled flag to control whether or not users can press the button. For example:

b.state(['disabled']) # set the disabled flag

b.state(['!disabled']) # clear the disabled flag

b.instate(['disabled']) # True if disabled, else False

b.instate(['!disabled']) # True if not disabled, else False

b.instate(['!disabled'], cmd) # execute 'cmd' if not disabledNote that these commands accept a list of state flags as their argument.

.b state disabled ;# set the disabled flag

.b state !disabled ;# clear the disabled flag

.b instate disabled ;# 1 if disabled, else 0

.b instate !disabled ;# 1 if not disabled, else 0

.b instate !disabled {mycmd} ;# execute 'mycmd' if not disabledb.state('disabled') ;# set the disabled flag

b.state('!disabled') ;# clear the disabled flag

b.instate('disabled') ;# true if disabled, else false

b.instate('!disabled') ;# true if not disabled, else false

b.instate('!disabled', 'cmd') ;# execute 'cmd' if not disabled$b->state("disabled"); # set the disabled flag

$b->state("!disabled"); # clear the disabled flag

$b->instate("disabled"); # 1 if disabled, else 0

$b->instate("!disabled"); # 1 if not disabled, else 0

$b->instate("!disabled", sub {mycmd}); # execute 'mycmd' if not disabledThe full list of state flags available to themed widgets is: active, disabled, focus, pressed, selected,

background, readonly, alternate, and invalid. These are described in the

themed widget reference. While all widgets have the same set of state flags, not all states

are meaningful for all widgets. It's also possible to get fancy in the state and instate methods

and specify multiple state flags at the same time.

The state and instate methods replace the older state configuration option (which took the values normal or

disabled).

That configuration option is actually still available for themed widgets, but "write-only," which means that

changing the option calls the appropriate state command. It's mainly intended as a convenience, so you can

specify a widget should be disabled when you first create it. However, any changes made using the new state

command do not update the configuration option. To avoid confusion, update your code to

use the state flags for all themed widgets.

Checkbutton

Checkbutton widgets.

A checkbutton widget is like a regular button that also holds a binary value of some kind (i.e., a toggle). When pressed, a checkbutton flips the toggle and then invokes its callback. Checkbutton widgets are frequently used to allow users to turn an option on or off.

Checkbuttons are created using the ttk.Checkbutton class. Typically, their contents and behavior are specified at the same time:

measureSystem = StringVar()

check = ttk.Checkbutton(parent, text='Use Metric',

command=metricChanged, variable=measureSystem,

onvalue='metric', offvalue='imperial')Checkbuttons are created using the ttk::checkbutton command. Typically, their contents and behavior are specified at the same time:

ttk::checkbutton .check -text "Use Metric" -command "metricChanged"

-variable measuresystem -onvalue metric -offvalue imperialCheckbuttons are created using the Tk::Tile::CheckButton class. Typically, their contents and behavior are specified at the same time:

$measureSystem = TkVariable.new

check = Tk::Tile::CheckButton.new(parent) {text 'Use Metric';

command 'metricChanged'; variable $measureSystem;

onvalue 'metric'; offvalue 'imperial'}Checkbuttons are created using the new_ttk__checkbutton method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__checkbutton.

Typically, their contents and behavior are specified at the same time:

$check = $parent->new_ttk__checkbutton(-text => "Use Metric", -command => sub {metricChanged},

-variable => \$measuresystem, -onvalue => "metric", -offvalue => "imperial");Checkbuttons use many of the same options as regular buttons but add a few more. The text, textvariable,

image, and compound configuration options control the display of the label (next to the checkbox itself).

Similarly, the command option lets you specify a command to be called every time a user toggles the checkbutton; and the

invoke method will also execute the same command.

The state and instate methods allow you to manipulate the disabled state flag to enable or disable the checkbutton.

Widget value

Unlike regular buttons, checkbuttons also hold a value. We've seen how the textvariable option links

the label of a widget to a variable. The variable option for checkbuttons behaves similarly, except

it links a variable to the widget's current value. The variable is updated whenever the widget is toggled. By default,

checkbuttons use a value of 1 when checked and 0 when not checked. These can be changed to

something else using the onvalue and offvalue options.

A checkbutton doesn't automatically set (or create) the linked variable. Therefore, your program needs to initialize it to the appropriate starting value.

What happens when the linked variable contains neither the onvalue or the offvalue (or even doesn't exist)? In that case,

the checkbutton is put into a special "tristate" or indeterminate mode. The checkbox might display a single dash in this mode instead of

being empty or holding a checkmark. Internally, the state flag alternate is set, which you can inspect

via the instate method:

check.instate(['alternate']).check instate alternatecheck.instate('alternate')$check->instate("alternate")So far, we've been using an instance of the StringVar class to attach variables to widgets. Tkinter provides other

variable classes that can hold booleans, integers, or floating-point numbers. You can always

use a StringVar (because the Tcl API that Tkinter uses is string-based) but can choose one of the others if

the data stored in it fits the type. All are subclasses of the base class Variable.

In the feet to meters example, we saw that you can call the get method of a Variable to retrieve its value or

the set method to provide a new value. You can also supply an initial value when you instantiate it.

s = StringVar(value="abc") # default value is ''

b = BooleanVar(value=True) # default is False

i = IntVar(value=10) # default is 0

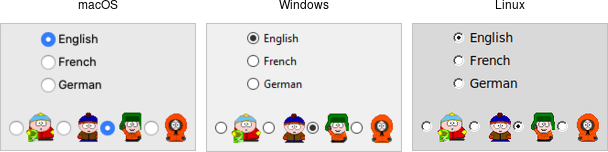

d = DoubleVar(value=10.5) # default is 0.0Radiobutton

Radiobutton widgets.

A radiobutton widget lets you choose between one of several mutually exclusive choices. Unlike a checkbutton, they are not limited to just two options. Radiobuttons are always used together in a set, where multiple radiobutton widgets are tied to a single choice or preference. They are appropriate to use when the number of options is relatively small, e.g., 3-5.

Radiobuttons are created using the ttk.Radiobutton class. Typically, you'll create and initialize several of them at once:

phone = StringVar()

home = ttk.Radiobutton(parent, text='Home', variable=phone, value='home')

office = ttk.Radiobutton(parent, text='Office', variable=phone, value='office')

cell = ttk.Radiobutton(parent, text='Mobile', variable=phone, value='cell')Radiobuttons are created using the ttk::radiobutton command. Typically, you'll create and initialize several of them at once:

ttk::radiobutton .home -text "Home" -variable phone -value home

ttk::radiobutton .office -text "Office" -variable phone -value office

ttk::radiobutton .cell -text "Mobile" -variable phone -value cellRadiobuttons are created using the Tk::Tile::RadioButton class. Typically, you'll create and initialize several of them at once:

$phone = TkVariable.new

home = Tk::Tile::RadioButton.new(parent) {text 'Home'; variable $phone; value 'home'}

office = Tk::Tile::RadioButton.new(parent) {text 'Office'; variable $phone; value 'office'}

cell = Tk::Tile::RadioButton.new(parent) {text 'Mobile'; variable $phone; value 'cell'}Radiobuttons are created using the new_ttk__radiobutton method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__radiobutton. Typically, you'll create and initialize several of them at once:

$home = $parent->new_ttk__radiobutton(-text => "Home", -variable => \$phone, -value => "home");

$office = $parent->new_ttk__radiobutton(-text => "Office", -variable => \$phone, -value => "office");

$cell = $parent->new_ttk__radiobutton(-text => "Mobile", -variable => \$phone, -value => "cell");Radiobuttons share most of the same configuration options as checkbuttons. One exception is that the

onvalue and offvalue options are replaced with a single value option.

Each radiobutton in the set will have the same linked variable but a different value.

When the variable holds the matching value, that radiobutton will visually indicate it is selected.

If it doesn't match, the radiobutton will be unselected.

If the linked variable doesn't exist, or you don't specify one with the variable option,

radiobuttons also display as "tristate" or indeterminate. This can be checked via the alternate state flag.

Entry

Entry widgets.

An entry widget provides users with a single-line text field where they can type in a string value. These can be just about anything: a name, a city, a password, social security number, etc.

Entries are created using the ttk.Entry class:

username = StringVar()

name = ttk.Entry(parent, textvariable=username)Entries are created using the ttk::entry command:

ttk::entry .name -textvariable usernameEntries are created using the Tk::Tile::Entry class:

$username = TkVariable.new

name = Tk::Tile::Entry.new(parent) { textvariable $username }Entries are created using the new_ttk__entry method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__entry:

$name = $parent->new_ttk__entry(-textvariable => \$username);A width configuration option may be specified to provide the number of

characters wide the entry should be. This allows you, for example, to display a shorter

entry for a zip or postal code.

name['width'] = 25.name configure -width 25name['width'] = 25$name->configure(-width => 25);Entry contents

We've seen how checkbutton and radiobutton widgets have a value associated with them.

Entries do as well. That value is usually accessed through a linked variable

specified by the textvariable configuration option.

Unlike the various buttons, entries don't have a text or image beside them to identify them. Use a separate label widget for that.

You can also retrieve or change the value of the entry widget without going

through the linked variable. The get method returns the current value.

The delete method allows you to remove part of all of the text in the widget, specified by a character position (0 for the first character, 1 for the second, etc.); the special end refers to the position just past the last character. The insert method allows you to add new text ata given position.

print(f'current value is {name.get()}')

name.delete(0, 'end') # delete between two indices, 0-based

name.insert(0, 'your name') # insert new text at a given indexputs "current value is [.name get]"

.name delete 0 end ; # delete between two indices, 0-based

.name insert 0 "your name" ; # insert new text at a given indexputs ("current value is #{name.get}")

name.delete(0, end) ; # delete between two indices, 0-based

name.insert(0, 'your name') ; # insert new text at a given indexprint "current value is " . $name->get;

$name->delete(0, "end"); # delete between two indices, 0-based

$name->insert(0, "your name"); # insert new text at a given indexWatching for changes

Entry widgets don't have a command option to invoke a

callback whenever the entry is changed. To watch for changes, monitor

the linked variable via the trace add method. See also "Validation" below.

def it_has_been_written(*args):

...

username.trace_add("write", it_has_been_written)proc it_has_been_written {args} {...}

trace add variable username write it_has_been_writtendef it_has_been_written()

...

end

$username.trace("write", proc{it_has_been_written})sub it_has_been_written {...}

Tkx::trace("add", "variable", \$username, "write", sub{it_has_been_written});You'll be fine if you stick with simple uses of trace_add like that shown above. You might want to know that

this is a small part of a much more complex system for observing variables and invoking callbacks when they are read, written,

or deleted. You can trigger multiple callbacks, add or delete them (trace_remove), and introspect

them (trace_info).

These methods replace a now-deprecated set of older methods (trace, trace_variable, trace_vdelete,

and trace_vinfo) that should not be used.

StringVar (or any subclass of Variable).

Both the older and newer tracing tools are a very thin (and not terribly Pythonic) front end to Tcl's trace command.

Passwords

Entries can be used for passwords, where the actual contents are displayed as a bullet or other symbol.

To do this, set the show configuration option to the character you'd like to display.

passwd = ttk.Entry(parent, textvariable=password, show="*")ttk::entry .passwd -textvariable password -show "*"passwd = Tk::Tile::Entry.new(parent) { textvariable $password; show "*"}$passwd = $parent->new_ttk__entry(-textvariable => \$password, show => "*");Widget states

Like the various buttons, entries can also be put into a disabled state via the state command (and queried

with instate). Entries can also use the state flag readonly; if set, users cannot change the entry,

though they can still select the text in it (and copy it to the clipboard). There is also an invalid

state, set if the entry widget fails validation, which leads us to...

Validation

Users can type any text they like into an entry widget. However, if you'd like to restrict what they can type into the entry, you can do so with validation. For example, an entry might only accept an integer or a valid zip or postal code.

Your program can specify what makes an entry valid or invalid, as well as when to check its validity. As we'll see soon, the two are related. We'll start with a simple example, an entry that can only hold an integer up to five digits long.

The validation criteria are specified via an entry's validatecommand configuration option. You supply a piece of

code whose job is to validate the entry. It functions like a widget callback or event binding, except that it returns

True or False (whether or not the entry is valid). To start, we'll validate the entry on every keystroke; this

is specified by providing a value of key to the validate configuration option.

import re

def check_num(newval):

return re.match('^[0-9]*$', newval) is not None and len(newval) <= 5

check_num_wrapper = (root.register(check_num), '%P')

num = StringVar()

e = ttk.Entry(root, textvariable=num, validate='key', validatecommand=check_num_wrapper)

e.grid(column=0, row=0, sticky='we')proc check_num {newval} {

return [expr {[regexp {^[0-9]*$} $newval] && [string length $newval]<=5}]

}

ttk::entry .e -textvariable num -validate key -validatecommand "check_num %P"

grid .e -column 0 -row 0 -sticky wedef check_num(newval)

return /^[0-9]*$/.match(newval) && newval.length <= 5

end

num = TkVariable.new

e = Tk::Tile::Entry.new(root) {textvariable num; validate 'key'; validatecommand [proc{|v| check_num(v)}, '%P']}

e.grid :column => 0, :row => 0, :sticky => 'we'sub check_num {

my ($newval) = @_;

return $newval =~ /^[0-9]*$/ && length($newval) <= 5 ? 1 : 0;

}

$e = $mw->new_ttk__entry(-textvariable => \$num, -validate => 'key', -validatecommand => [\&check_num, Tkx::Ev('%P')]);

$e->g_grid(-column => 0, -row => 0, -sticky => 'we');Our check function accepts a single parameter, the new value of the entry if the validation succeeds We'll use a simple regular expression and a length

check to determine if the change is valid. To reject the change, our validation command can return a False value, leaving the entry unchanged.

As with event bindings, there are a number of parameters that provide more information about the conditions that triggered the validation.

To make them available, we need to access them via percent substitutions. We used one of these here:

%P is the new value of the entry (again, if the validation succeeds).

You'll notice some ugly code gymnastics are required to pass that new value to our validation function.

Taking advantage of these percent substitutions requires some gymnastics. We have to first choose which percent substitutions

we're interested in. The register method (callable on any widget) creates a Tcl procedure which will call our Python function.

The percent substitutions we've chosen will be passed to it as parameters.

Incidentally, Tk events use a very similar mechanism of percent substitutions to pass event parameters to bindings. However, Tkinter encapsulated all these parameters into an event object that is passed to the callback. Tkinter abstracts away all the details about percent substitutions so you don't have to worry about them. Unfortunately, there's no equivalent abstraction for validation callbacks.

Let's extend our example so that the entry will accept a US zip code, formatted as "#####" or "#####-####" ("#" can be any digit). We'll still do some validation on each keystroke (only allowing entry of numbers or a hyphen). However, we can no longer fully validate the entry on every keystroke. If they've just typed the first digit, it's not valid yet. If we reject the change after this first character, they'll never be able to enter a complete zip code.

So full validation will only happen when the entry loses focus (e.g., a user tabs away from it). Tk refers to this as revalidation, in contrast with prevalidation (accepting changes on each keystroke).

How should we respond to errors? Let's add a message reminding users of the format. It will appear if they type a wrong key or tab away from the entry when it's not holding a valid zip code. We'll remove the message when they return to the entry or type a valid key. We'll also add a (dummy) button to "process" the zip code, which will be disabled unless the zip entry is valid. Finally, we'll also add a "name" entry so you can tab away from the zip entry.

import re

errmsg = StringVar()

formatmsg = "Zip should be ##### or #####-####"

def check_zip(newval, op):

errmsg.set('')

valid = re.match('^[0-9]{5}(\-[0-9]{4})?$', newval) is not None

btn.state(['!disabled'] if valid else ['disabled'])

if op=='key':

ok_so_far = re.match('^[0-9\-]*$', newval) is not None and len(newval) <= 10

if not ok_so_far:

errmsg.set(formatmsg)

return ok_so_far

elif op=='focusout':

if not valid:

errmsg.set(formatmsg)

return valid

check_zip_wrapper = (root.register(check_zip), '%P', '%V')

zip = StringVar()

f = ttk.Frame(root)

f.grid(column=0, row=0)

ttk.Label(f, text='Name:').grid(column=0, row=0, padx=5, pady=5)

ttk.Entry(f).grid(column=1, row=0, padx=5, pady=5)

ttk.Label(f, text='Zip:').grid(column=0, row=1, padx=5, pady=5)

e = ttk.Entry(f, textvariable=zip, validate='all', validatecommand=check_zip_wrapper)

e.grid(column=1, row=1, padx=5, pady=5)

btn = ttk.Button(f, text="Process")

btn.grid(column=2, row=1, padx=5, pady=5)

btn.state(['disabled'])

msg = ttk.Label(f, font='TkSmallCaptionFont', foreground='red', textvariable=errmsg)

msg.grid(column=1, row=2, padx=5, pady=5, sticky='w')set ::formatmsg "Zip should be ##### or #####-####"

proc check_zip {newval op} {

set ::errmsg ""

set valid [expr {[regexp {^[0-9]{5}(\-[0-9]{4})?$} $newval]}]

.f.btn state [expr {$valid ? "!disabled" : "disabled"}]

if {$op=="key"} {

set ok_so_far [expr {[regexp {^[0-9\-]*$} $newval] && [string length $newval]<=10}]

if {!$ok_so_far} {set ::errmsg $::formatmsg }

return $ok_so_far

} elseif {$op=="focusout"} {

if {!$valid} {set ::errmsg $::formatmsg}

}

return $valid

}

grid [ttk::frame .f] -column 0 -row 0

grid [ttk::label .f.l1 -text "Name:"] -column 0 -row 0 -padx 5 -pady 5

grid [ttk::entry .f.e1] -column 1 -row 0 -padx 5 -pady 5

grid [ttk::label .f.l -text "Zip:"] -column 0 -row 1 -padx 5 -pady 5

ttk::entry .f.e -textvariable zip -validate all -validatecommand "check_zip %P %V"

grid .f.e -column 1 -row 1 -padx 5 -pady 5

grid [ttk::button .f.btn -text Process] -column 2 -row 1 -padx 5 -pady 5

.f.btn state disabled

ttk::label .f.msg -font TkSmallCaptionFont -foreground red -textvariable errmsg

grid .f.msg -column 1 -row 2 -padx 5 -pady 5 -sticky w$errmsg = TkVariable.new

$formatmsg = "Zip should be ##### or #####-####"

def check_zip(newval, op)

$errmsg.value = ''

valid = /^[0-9]{5}(\-[0-9]{4})?$/.match(newval)

$btn.state(valid ? '!disabled' : 'disabled')

if op=='key'

ok_so_far = /^[0-9\-]*$/.match(newval) && newval.length <= 10

$errmsg.value = $formatmsg if not ok_so_far

return ok_so_far

elsif op=='focusout'

$errmsg.value = $formatmsg if not valid

end

return valid

end

zip = TkVariable.new

f = Tk::Tile::Frame.new(root)

f.grid :column => 0, :row =>0

Tk::Tile::Label.new(f) {text 'Name:'}.grid :column => 0, :row => 0, :padx => 5, :pady => 5

Tk::Tile::Entry.new(f).grid :column => 1, :row => 0, :padx => 5, :pady => 5

Tk::Tile::Label.new(f) {text 'Zip:'}.grid :column => 0, :row => 1, :padx => 5, :pady => 5

e = Tk::Tile::Entry.new(f) {textvariable zip; validate 'all'; validatecommand [proc{|v,o| check_zip(v,o)}, '%P', '%V']}

e.grid :column => 1, :row => 1, :padx => 5, :pady => 5

$btn = Tk::Tile::Button.new(f) {text 'Process'}

$btn.grid :column => 2, :row => 1, :padx => 5, :pady => 5

$btn.state 'disabled'

msg = Tk::Tile::Label.new(f) {font 'TkSmallCaptionFont'; foreground 'red'; textvariable $errmsg}

msg.grid :column => 1, :row => 2, :padx => 5, :pady => 5, :sticky => 'w'our $errmsg = "";

our $formatmsg = "Zip should be ##### or #####-####";

sub check_zip {

my ($newval,$op) = @_;

$errmsg = "";

$valid = $newval =~ /^[0-9]{5}(\-[0-9]{4})?$/;

$btn->state($valid ? "!disabled" : "disabled");

if ($op eq "key") {

$ok_so_far = $newval =~ /^[0-9\-]*$/ && length($newval) <= 10;

$errmsg = $formatmsg if not $ok_so_far;

return $ok_so_far ? 1 : 0;

} elsif ($op eq "focusout") {

$errmsg = $formatmsg if not $valid;

}

return $valid ? 1 : 0;

}

$f = $mw->new_ttk__frame();

$f->g_grid(-column => 0, -row => 0);

$f->new_ttk__label(-text => 'Name:')->g_grid(-column => 0, -row => 0, -padx => 5, -pady => 5);

$f->new_ttk__entry()->g_grid(-column => 1, -row => 0, -padx => 5, -pady => 5);

$f->new_ttk__label(-text => 'Zip:')->g_grid(-column => 0, -row => 1, -padx => 5, -pady => 5);

$e = $f->new_ttk__entry(-textvariable => \$zip, -validate => 'all', -validatecommand => [\&check_zip, Tkx::Ev('%P', '%V')]);

$e->g_grid(-column => 1, -row => 1);

our $btn = $f->new_ttk__button(-text => 'Process:');

$btn->g_grid(-column => 2, -row => 1, -padx => 5, -pady => 5);

$btn->state('disabled');

$msg = $f->new_ttk__label(-font => 'TkSmallCaptionFont', -foreground => 'red', -textvariable => \$errmsg);

$msg->g_grid(-column => 1, -row => 2, -padx => 5, -pady => 5, -sticky => 'w');Notice that the validate configuration option has been changed from key to all.

That arranges for the validatecommand callback to be invoked on not only keystrokes but other triggers.

The trigger is passed to the callback using the %V percent substitution.

The callback differentiated between key and focusout triggers (you can also check for focusin).

There are a few more things to know about validation. First, if your validatecommand ever generates an error

(or doesn't return a boolean), validation will be disabled for that widget. Your callback can modify the entry, e.g.,

change its textvariable. You can ask the widget to validate at any time by calling

its validate method, which returns true if validation passes (the %V substitution is set to forced).

There is an invalidcommand configuration option (which works like validatecommand) that is called whenever

validation fails. You can use it to accomplish nasty things like forcing the focus back on the widget that didn't validate.

In practice, it's rarely used. As mentioned earlier, the entry's invalid state flag (which can be checked via

the instate invalid method) is automatically updated as validation succeeds or fails.

Other percent substitutions allow you to get the entry's contents prior to editing (%s), differentiate between insert and delete (%d), where an insert or delete occurs (%i), what is being inserted or deleted (%S), the

current setting of the validate option (%v) and the name of the widget (%W).

Combobox

Combobox widgets.

A combobox widget combines an entry with a list of choices. This lets users either choose from a set of values you've provided (e.g., typical settings), but also put in their own value (e.g., for less common cases).

Comboboxes are created using the ttk.Combobox class:

countryvar = StringVar()

country = ttk.Combobox(parent, textvariable=countryvar)Comboboxes are created using the ttk::combobox command:

ttk::combobox .country -textvariable countryComboboxes are created using the Tk::Tile::Combobox class:

$countryvar = TkVariable.new

country = Tk::Tile::Combobox.new(parent) { textvariable $countryvar }Comboboxes are created using the new_ttk__combobox method, a.k.a. Tkx::ttk__combobox:

$country = $parent->new_ttk__combobox(-textvariable => \$countryvar);Like entries, the textvariable option links a variable in your program to the

current value of the combobox. As with other widgets, you should initialize

the linked variable in your own code.

A combobox will generate a <<ComboboxSelected>> virtual event that you can bind to whenever its value changes.

(You could also trace changes on the textvariable, as we've seen in the previous few widgets we covered.

Binding to the event is more straightforward, and so tends to be our preferred choice.)

country.bind('<<ComboboxSelected>>', function)bind .country <<ComboboxSelected>> { script }country.bind("<ComboboxSelected>") { script }$country->g_bind("<<ComboboxSelected>>", sub { script });Predefined values

You can provide a list of values that users can choose from using the values configuration

option:

country['values'] = ('USA', 'Canada', 'Australia').country configure -values [list USA Canada Australia]country['values'] = [ 'USA', 'Canada', 'Australia']$country->configure(-values => "USA Canada Australia");If set, the readonly state flag will restrict users to making choices only from the list

of predefined values but not be able to enter their own (though if the current value of the

combobox is not in the list, it won't be changed).

country.state(["readonly"]).country state readonlycountry.state('readonly')$country->state("readonly");If you're using the combobox in readonly mode, I'd recommend

that when the value changes (i.e., on a <<ComboboxSelected>> event), that

you call the selection_clear method. It looks a bit odd visually

without doing that.

You can also get the current value using the get method and change the current value using the set

method (which takes a single argument, the new value).

To complement the get and set methods, you can also use the current method to determine

which item in the predefined values list is selected. Call current with no arguments; it will

return a 0-based index into the list or -1 if the current value is not in the list. You can select

an item in the list by calling current with a single 0-based index argument.

Want to associate some other value with each item in the list so that your program can use one value internally, but it gets displayed in the combobox as something else? You'll want to have a look at the section entitled "Keeping Extra Item Data" when we get to the discussion of listboxes in a couple of chapters from now.